By Ross Pullen, Senior Director, Head of Product Development, Cboe

Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) have become increasingly popular among investors due to their ease of access, diversification, and low fees. Behind the scenes, there is a group of specialised firms known as Market Makers (MMs) that play a crucial role in providing liquidity and pricing for ETFs. In this first article of a series with Cboe Australia, this will explore what happens behind the scenes for MMs to offer prices in ETFs, day in and day out.

MMs are sophisticated technology driven businesses that usually trade in multiple countries. They’re experts at managing risk (or they won’t last long) and provide an essential service. If you’ve ever bought an ETF, it is likely that a MM was on the other side of that trade.

A couple of points about MMs, they generally:

- Are appointed by an ETF issuer and/or registered with an exchange like Cboe and have minimum quoting metrics (e.g. max. Bid/Ask spread and min. value);

- Need an ASIC AFSL authorised for market making activities or exemption;

- Are eligible for ASIC exemption from the naked short sale prohibition;

- Have access to wholesale prices and costs (e.g. FX) that may result in better prices than retail investors are able to access directly;

- Don’t seek to hold risk;

- Compete against each other to offer the best price for investors;.

The most common type of market making in Australia is called External Market Making (EMM). EMM is used for ETFs which provide either (a) daily full portfolio disclosure; or (b) a daily pricing basket with maximum quarterly two (2) month delayed full portfolio disclosure.

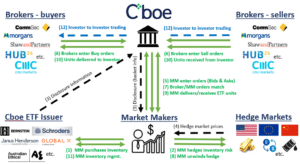

Diagram 1 below provides a simplified explanation of how an EMM trade is generally undertaken. Asset price risk is avoided by the MM and prices offered are a function of the underlying assets of the ETF (like they would be if an investor bought the underlying assets directly).

Diagram 1: Simplified EMM “Trade” Overview

Steps:

- The MM creates inventory by creating ETF units with the issuer @ end-of-day prices (business as usual for any open-ended fund);

- The MM immediately hedges that risk (being long the ETF units) so its overall “market price-change risk” exposure is close to nil, e.g., A MM might be long $500 worth of S&P 500 tracking ETF units and hedge by going short $500 of a S&P 500 future;

- The ETF issuer discloses daily NAV, portfolio information and may publish an iNAV on their website (a live indication of an ETF unit’s NAV);

- The MM sources hedge prices;

- The market maker prices the ETF using the portfolio info and hedge market prices. This may include futures or other correlated price proxies for closed markets; Based on hedge prices, the MM enters Bids/Asks on Cboe in the ETF (complying with minimum prescribed liquidity metrics, e.g. max. Bid/Ask spread and min. value)

- Brokers enters buy and sell orders on behalf of investors

- MM & broker orders match on Cboe and trade; the MM immediately closes a corresponding hedge (e.g. if $100 of S&P 500 tracking ETF units was sold, the MM may close $100 of short exposure to S&P 500 futures);

- The MM:

- Delivers ETF units if the MM sold ETF units; or,

- Receives ETF units if the MM purchased ETF units;

- Investors:

- Deliver ETF units if the investor sold ETF units; or

- Receive ETF units if the investor purchased ETF units;

- Periodically, the MM will manage its inventory. E.g. if a MM generally holds a $1mm of ETF units for inventory purposes and:

- Ended a day being long $5mm of ETF units, it may choose to redeem $4mm of ETF units with the issuer (while simultaneously exiting $4mm of a short hedge due to no longer being long $4mm of ETF units); or,

- Ended a day being long $200k of ETF units, it may choose to apply to create $800k of ETF units with the issuer to maintain adequate inventory (while simultaneously hedging with $800k of short exposure due to the additional ETF unit long exposure)

- Investors may trade between themselves via their brokers (within the Bid/Ask spread offered by the MM). This provides two (2) benefits:

- Permits investors to buy/sell units without the fund undertaking any operational activities (or tax impacts from consequent portfolio trading activities of creations/redemptions); and,

- Investors may possibly see pricing improvements within the spread and realising higher prices than actual creations/redemptions (especially where an underlying asset has a wider Bid/Ask spread).

The main point is really that ETF market making is both simple and complicated. There are a lot of steps above but the crux of ETF MM’ing comes down to:

- MMs arbitrage prices between the underlying assets of an ETF and the traded price of the ETF. They don’t compete against investors and investors may realise better prices when buying an ETF than may be available when buying an ETF’s underlying assets directly; and,

- MMs compete against each other to offer the best price. Generally the best price offered by any MM is the price that an investor trades at.

The next article of this series will look at how ETF prices are formed and what ensures that ETFs generally always trade at prices that are “at or close to NAV”.

Ross Pullen leads product development efforts to launch new markets at Cboe Australia, joining the organisation in October-2015. Prior to joining Cboe Australia, Mr Pullen led the AQUA team at the Australian Stock Exchange where he was responsible for ETF, Managed Fund, Hedge Fund & Warrant markets and ASX BookBuild. His background includes >16 years stock exchange experience and uniquely, he either led or was a member of teams which launched both of Australia’s ETF markets.