By John Forwood, Chief Investment Officer, Lowell Resources Funds Management Ltd

Lithium stocks have been the best performing resources companies on the ASX over the past three years, up over 250%. The EV revolution, part of the global decarbonisation push, underlies the lithium market. From a battery perspective, by 2030 lithium will face the greatest supply and demand gap of any mineral, according to McKinsey. But battery chemistries are evolving almost daily, while at the same time mining companies are rushing to increase supply of lithium.

So, what will be the next commodity to boom?

Lithium equities

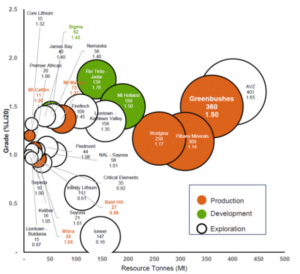

Australia is the world’s largest lithium miner, producing 45% of the world’s lithium in 2022. The biggest lithium mines in Australia are all hard-rock spodumene pegmatite mines in WA: Greenbushes (the world’s largest, which is owned by Tianqi Lithium Corporation, IGO Limited and Albemarle Corporation), Wodgina (owned by Mineral Resources and Albemarle) and Pilgangoora (owned by Pilbara Minerals).

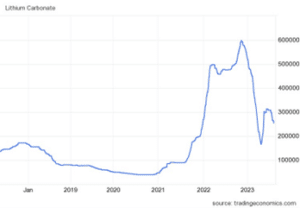

Pilbara Minerals is the largest pure-play ASX listed lithium company. Since March 2020, its share price has risen from 15 cents to over $5.00/sh, a rise of over 30 times. In that period, the lithium carbonate price in China rose over 12 times. Other ASX lithium focused companies share prices have also surged, such as Lowell Resources Fund investments Liontown Resources and Azure Minerals, both up nearly 40x.

Figure: Global Hardrock Lithium Projects (2022)

In terms of new investors in the upstream resources sector, car companies are one of the most remarkable. Many would have never thought they’d see Maserati investing in a development-stage mining company, but in 2022 Stellantis (owner of the Fiat, Chrysler, Peugeot, Maserati, and Jeep brands) invested A$76m in Vulcan Energy, which plans to produce lithium brines in the Rhine Valley. Similarly in early 2023, General Motors announced a US$650m investment in Lithium Americas Corp to help it develop Nevada’s Thacker Pass lithium mining project, which holds enough of the battery metal to build one million electric vehicles annually.

Oil and gas companies have also looked to deploy capital into battery minerals projects. Exxon has recently been reported to be entering the lithium production sector, as a supplier to Tesla, Ford and Volkswagen. Exxon is assessing the potential to produce lithium from groundwater brines, by applying some of its oil drilling and production expertise.

Figure: Lithium Carbonate price in China (CNY/t)

What is the ‘Next Lithium’?

Some of the key elements which have made lithium equities a market darling arguably include:

- a commodity important to the energy transition

- a large exposure to the electric vehicle market

- classification as a “critical mineral”, and forecasts of large supply-demand gaps

- preferably mineral offtake uncontracted and available to western end-users

- relatively low capital barriers to initial cashflow, and low operating costs driven by simple processing

- a relatively commonly occurring mineral

- and, most importantly, near term commodity price rises.

A few commodities which could have similar market booms to lithium include uranium, graphite and copper.

Uranium

While not directly used in EV’s, nuclear is becoming a more important part of the energy transition as governments face the reality that investment in renewables is not going to meet decarbonisation objectives due to limitations on transmission, batteries and firming capacity. There are 59 new nuclear reactors being constructed around the globe, adding to the existing fleet of 436 reactors.

Uranium equities have the capacity to produce stratospheric returns. Between 2002 and 2007, when the uranium price went from US$8/lb to US$140/lb, ASX-listed Paladin Energy’s share price rose from 1cps to $8.00/sh. However, with the uranium price currently around US$55/lb, some of the upside has already been priced into uranium development stocks. Further, the process to permit a new uranium mine is tortuous and processing is more complex.

Graphite

Graphite has many of the attributes of lithium, and graphite represents around half of the weight of a lithium-ion battery, or 7-10 times the amount of lithium. It is a commonly occurring mineral with low capital and operating costs to develop and mine. Graphite prices have remained relatively stable, and graphite equities in many cases are trading at deep discounts to their underlying project NPV’s.

Importantly, battery-related demand for graphite breached a key inflection point at the end of 2022 when it rose to over 50% of the total market. When the cobalt and lithium markets crossed the 50% barrier in 2016 and 2020 respectively, price increases of 350% and 1,300% followed for those commodities over the next two years. On the other hand, qualification of graphite concentrate product to offtakers is a lengthy multi-year process, and the market is completely dominated by China.

Copper

There is no decarbonisation without electrification, and, at least on current technology, there can be no widescale electrification without copper. EVs can use up to three and a half times as much copper when compared to an internal combustion engine (ICE) passenger car. Copper is already a well-established and very large metal market (third in size in terms of value, behind iron ore and gold, and about 20 times the size of the lithium market), and many forecasters are predicting up to a 30% supply-demand shortfall developing after 2025.

While new production is expected over the period 2023-2025, visible copper stockpiles in exchange warehouses are currently at decade lows. Copper is not rare, but new discoveries large enough to make a significant contribution to global supply are becoming very infrequent, while permitting delays are growing. Capital and operating costs for copper mining are generally higher than for lithium.

Conclusion

The lithium sector has been one of the few bright spots in the junior to mid-tier resources sector on the ASX. Enormous profits are being made by both producing companies such as Pilbara Minerals, and by investors in developers such as Liontown and Azure Minerals. The energy transition has driven the demand for lithium, but many other minerals are “critical” to this transition. It is virtually certain that as the world decarbonises, other minerals such as uranium, graphite or copper will see similar booms.

Lowell Resources Fund Management (LRFM) manages the ASX-listed Lowell Resources Fund (ASX.LRT) portfolio of exploration and development companies operating in precious and base metals, specialty metals and the energy sector. www.lrfm.com.au. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor or constitute advice. No fund or stock mentioned in this article constitutes an offer or inducement to enter into any investment activity.